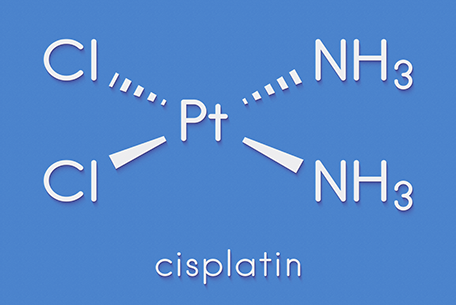

Building on this knowledge, scientists found that cancer cells behaved in a similar way – the platinum compound causing them to die off. From here, several years of intense research led to the development of cisplatin, selected from a range of possible molecular combinations to create an optimal compromise between toxicity and efficacy, which began clinical trials in the UK in 1971.

Cisplatin, with a 65 per cent platinum content, has well known side effects and certain cancers can develop a resistance to it. Despite these drawbacks, it is still a front-line cancer treatment, although additional platinum-based therapies have since been developed to mitigate against these issues. Carboplatin, containing 52.5 per cent platinum, was approved in 1986 and is used mainly to treat ovarian and lung cancers. Available since 1996, Oxaliplatin with 49 per cent platinum is used to treat colorectal cancer.

Working alongside newer therapies

Today, around half of all patients undergoing treatment for cancer receive platinum-based chemotherapy as a first-line treatment that can work alongside newer technologies such as hormonal therapy and immunotherapy.

New platinum formulations are currently in development and the hope is to improve targeting and reduce toxicity further, as well as producing a medication that can be taken orally, allowing patients to be treated at home.

Demand for platinum in medical applications, including pharmaceuticals, currently stands at around 240,000 oz, 3.2 per cent of total annual platinum demand in 2018 (7,380,000 oz). This demand is likely to increase due to factors including population growth, changing demographics towards an ageing population and increased access to medical care in both developed and developing countries.